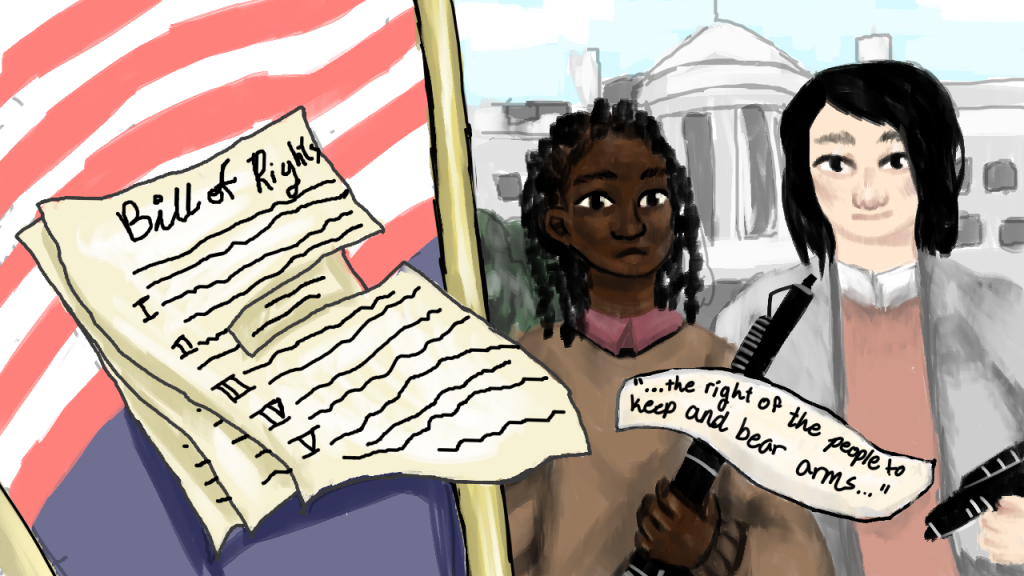

(Emory Wheel / Angel Li)

Ratified in 1791, the Second Amendment is one of the most integral American principles that has shaped this nation’s history, social ideals and national value system. The Second Amendment states, “a well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” However, a consensus on the application of this fundamental right has become increasingly nuanced in the wake of America’s uniquely persistent gun violence problem.

We are once again confronted with the issue of guns in America. We should leverage the constitution’s political power to explore new avenues of public discourse and political organizing among minorities that centers gun education as a viable solution to address gun violence than restrictive gun reform.

At the heart of the gun debate is not simply a dispute regarding the effects of gun violence on public safety but also the legal avenue, or lack thereof, to address gun violence. Moreover, the actors mediating this highly contentious discussion and the effective ramifications of prior gun legislation are also contributing factors to the current condition of America’s pervasive gun ideologies and strongest proponents. In recent years, public discourse has forced this discussion into a gridlock. Those paradigmatic gun-rights activists who denounce big government and promote hyper-individualism are in direct opposition to gun reformists who generally believe that the government is both competent and benevolent enough to effectively address such national grievances.

Bipartisan support for the promotion of public safety has moved well beyond the realm of possibility in our current political landscape into a stubborn and often unimaginative display of band-aid solutions, and the constitutional muster of the Second Amendment adds further barriers to addressing root causes of gun violence. Any attempt to ban guns and reform gun sale and distribution are seemingly futile. It is both impractical and unfeasible to anticipate meaningful legislative action from current lawmakers and lobbyists due to the sheer amount of guns currently in circulation on top of the deep-rooted and heavily racialized American gun culture.

The overwhelming dominance of political action groups such as the National Rifle Association (NRA) — with almost 5 million members nation-wide — has heavily influenced the gun debate. The NRA is the most prominent special interest lobby in support of the Second Amendment with a right-leaning bias. Their work consists of blocking gun restrictions on behalf of their conservative base, gun manufacturers’ generous financial contributions and political allies. Moreover, their youth programs educate countless students across the nation, and the law enforcement division incentivizes active and retired armed service members with a slew of benefits.

However, the NRA has also consistently failed to advocate for Black gun owners and gun violence victims. They ignore the harmful racial disparities between victims of gun violence in Stand Your Ground states. The NRA’s support for self-defense legislation, which promotes the use of deadly force rather than retreat in a dangerous altercation, was the major crux of the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the murder trial of un-armed Black teenager Trayvon Martin. As for the murder of Philando Castile, a legal gun owner whose death outraged Black NRA members, the leadership’s public response was tepid and dismissive.

The application of pro-gun laws is not equally applied across all groups. As Caroline E. Light, author of “Stand Your Ground: A History of America’s Love Affair With Lethal Self-Defense” states, “self-defensive lethal violence is steeped in a structure of power that tends to concentrate power in the hands of those who already have it.” Therefore, minority communities who seek to reclaim power within that structure should flood political lobbies in which they have been historically shunned. The political force of the Second Amendment could present legal pathways for radically re-imaging gun culture.

In response to these glaring hypocrisies, the National African American Gun Association, a competing organization, has experienced significant increases in membership over the last several years. Founded in 2015, the primary goal of the NAAGA is to distance themselves from the NRA. With over 30,000 active members (60% of whom are female), their mission is to encourage gun ownership and educate Black citizens on the historical nuances of their Second Amendment rights. They are currently considering creating a political action committee to further advance their agenda. These developments, as well as the rise of other Black pro-gun organizations, introduce a new element to the gun debate that centers the very individuals who have been historically disenfranchised as gun owners and victimized by gun violence.

Racially discriminatory gun reform is much older than our nation’s constitution. Since 1640, race-based laws have prevented both Black and Indigenous populations from access to firearms for fears of revolt against European colonial settlers. Even after the Civil War, the Black Codes were designed to prevent Black armament as a response to newly anointed African American citizenship. These legislative limitations further denied freed people’s ability to exercise their constitutional rights. Fast forward to the Civil Rights era, the creation of the original Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (later shortened to BPP) sparked more discussion about the use of firearms, specifically for political advancement. In 1967, 30 members of the BPP protested on the steps of the California State Capitol building. Lawmakers soon passed the Mulford Act that prohibited the open carry of loaded firearms because the Panthers were not publicly coded as armed patriots but instead as vigilantes. This piece of legislation was endorsed by the NRA and later signed into law by then Gov. Ronald Reagan.

More recently, federal gun legislation enacted by liberal politicians has arguably been ineffective or equally damaging. President Joe Biden’s record on gun control harks back to his involvement in the infamous Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. Due to constitutional limitations, the 1994 Assault Weapons Ban did very little to curb gun violence over long periods of time. Gun buyers, sellers and distributors found various loopholes in the legislation, such as sporterizing a banned weapon into a legal substitute. Legislation simply cannot keep up with the technological innovation of the manufacturing and ingenuity of illegal gun sale and distribution.

The only way to combat the NRA’s massive political influence and racialized American gun ideologies is to introduce more oppositional pro-gun organizations that understand the historical implications of gun rights and reform from an ameliorated perspective. This political strategy does not necessitate the increased ownership of guns, just minority advocacy for the fundamental principle. Any educated choice on whether to own a gun should be self-determined. By understanding this nuanced background, those that have been most affected by gun laws and gun violence can promote the well-being of their communities through representative education programs and political organizing. Doing so will not compromise the idea of gun ownership in America; in fact, it could very well revitalize the public safety discourse regarding guns in the U.S.

Viviana Barreto (22C) is from Covington, Georgia.

The Link LonkApril 05, 2021 at 08:06AM

https://emorywheel.com/wheel-debate-banning-guns-doesnt-work-but-more-minority-pro-gun-advocacy-does/

Wheel Debate: Banning Guns Doesn't Work, but More Minority Pro-Gun Advocacy Does - The Emory Wheel

https://news.google.com/search?q=Wheel&hl=en-US&gl=US&ceid=US:en

No comments:

Post a Comment